Randomly

Instructions and Tutorial

Instructions and Tutorial

A Library for Denoising Single-Cell Data with Random Matrix Theory

Randomly is a python package from the Rabadan Lab for denoising single-cell data using Random Matrix Theory.

Randomly is available on github in beta. The instructions for downloading and installing it, as well as a detailed tutorial, are given here.

Overview of the Problem

- Characterizing the different cell subtypes in heterogeneous populations and their evolution plays a central role in understanding complex systems like cancer or immune cells.

- Single-cell technologies1,2 offer the opportunity to identify new cell types and cellular states.

- There are biological and technical challenges that complicate the analysis of single-cell data:

- Problem 1: a lack of a complete quantitative understanding of different sorts of noise

- Problem 2: Sparsity of data due to low amounts of amplified genomic material

- Currently, there are two main methods to address these challenges:

- However, these methods make assumptions about gene expression distributions that are not well justified and may generate artifacts.

- To remedy this, Randomly develops a method for denoising single-cell data in a universal way:

- Objective 1: develop a statistical description of the noise in single-cell data that is insensitive to the specific details of gene expression in cells

- Objective 2: analyze and control the artifacts induced by sparsity in single-cell data

The Idea

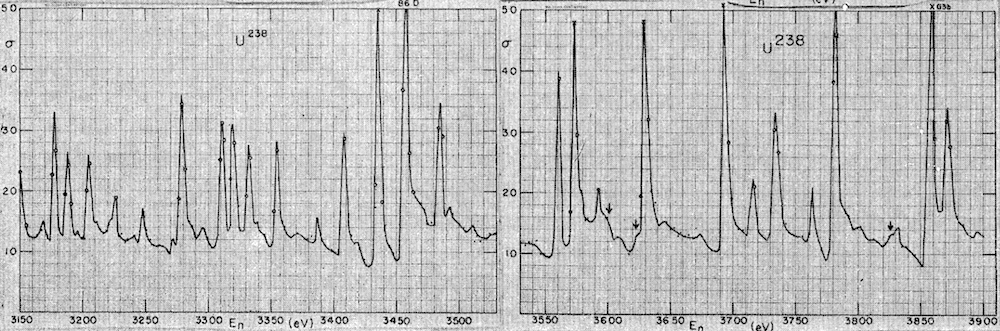

This problem is very similar to one addressed in nuclear physics in the 1950s and later in a variety of complex systems7. The physicist Eugene Wigner was interested in studying the energy spectra of heavy nuclei, such as uranium. Neutron scattering experiments revealed that the energy levels appear as peaks of the diffusion rate of neutrons as a function of the energy. This is shown in J.B. Garg et al.15:

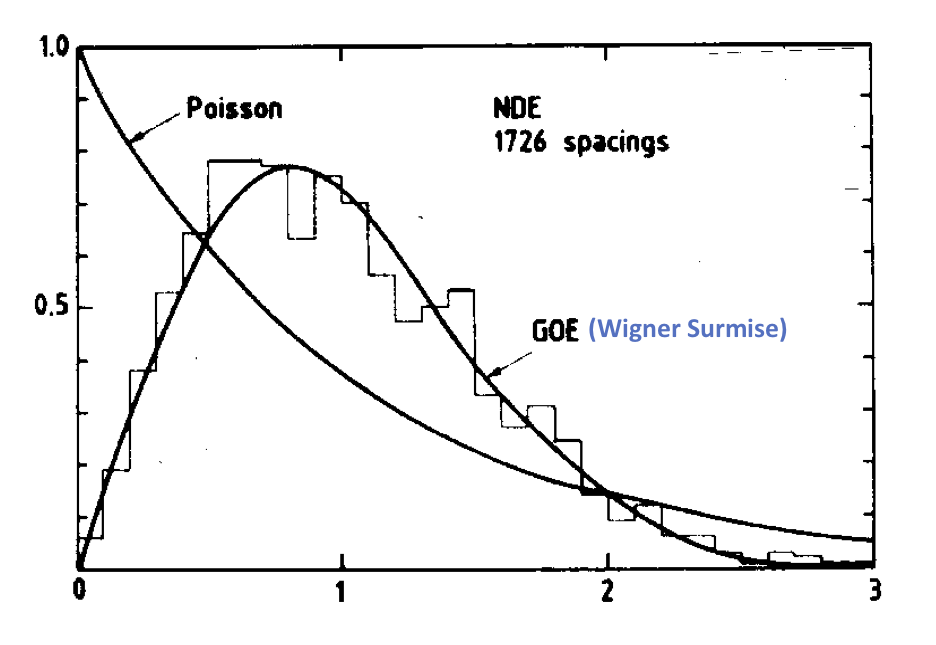

In the absence of any nuclear theory to explain this, Wigner became interested in studying the statistical distribution of the distance, s, between neighboring energy peaks. If the positions of the peaks were uncorrelated random numbers, then the distribution of distances should follow a Poisson law:

However, what Wigner found was that the statistical distribution is given by:

showing that the energy peaks were highly correlated. This is known as the Wigner Surmise. The following figure from O. Bohigas et al.16 illustrates this:

Wigner further postulated that his surmise is universal in the sense that it applies to any large, complicated quantum system regardless of the details of that system.

Later, starting in the 1960s, works by Dyson, Gaudin, Mehta, and others demonstrated that the Wigner Surmise is a consequence of the universality of Random Matrix Theory. Technically speaking, the eigenvalue statistics are independent of the distribution used to generate the matrix elements.

Recently, Random Matrix Theory has found applications in a diverse range of complex physical and mathematical systems, including zeros of the Riemann Zeta Function, quantum chaotic systems, quantum chromodynamics, string theory, cosmology, transport in disordered systems, crystal growth, telecommunications, finance theory, and neuroscience...

For the first time, we have extended this to the field of genomics.

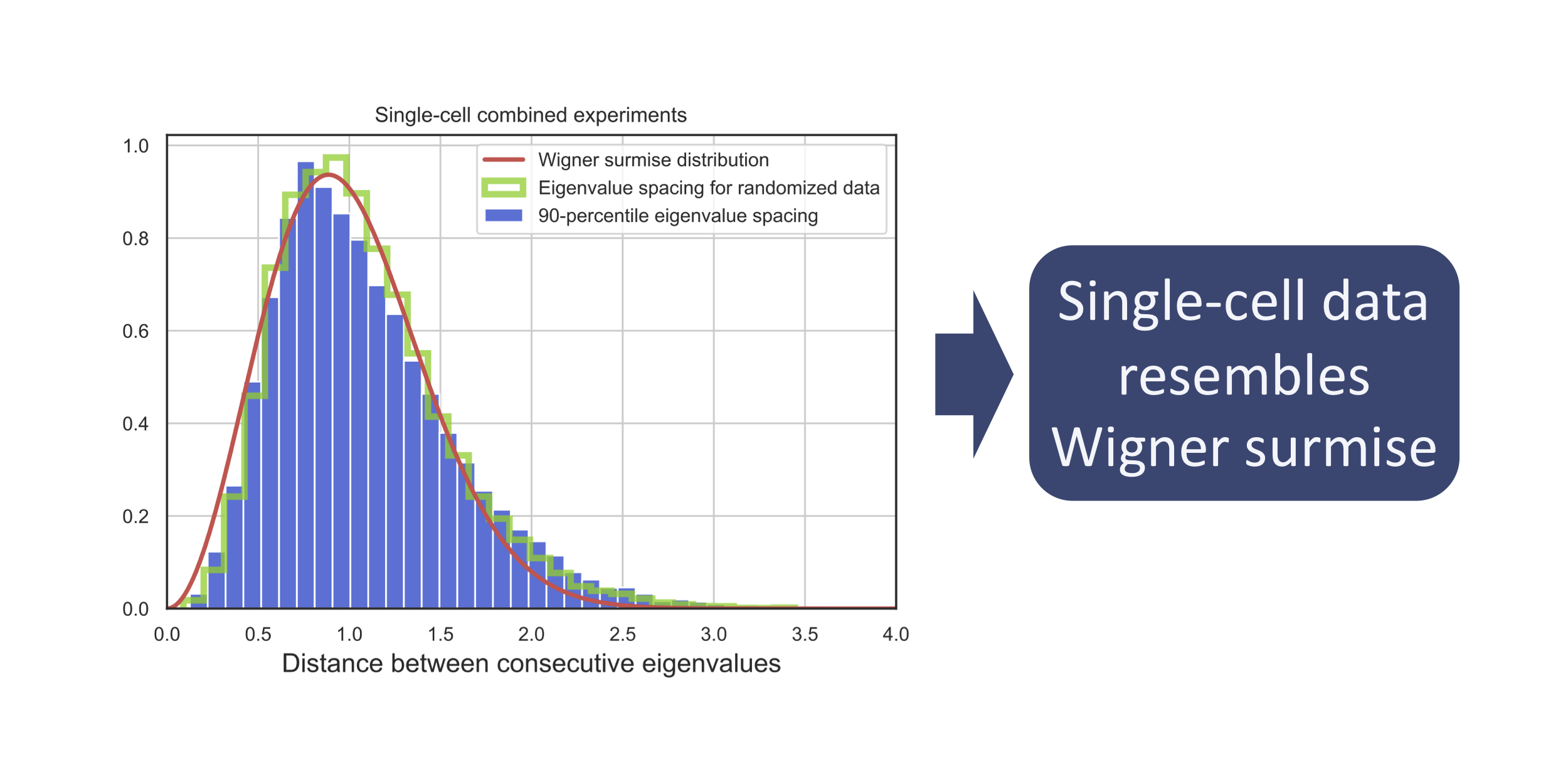

We observe that single-cell data resembles the Wigner Surmise:

As Dyson observed7, the complex systems described by Random Matrix Theory are a

“black box in which a large number of particles are interacting according to unknown laws.”Happily, this is the essence of Systems Biology, which studies systems with a large number of components, such as genes, bio-molecules or cells, interacting according to unknown laws.

Random Matrix Theory in 1 Minute

- For a given single-cell dataset X with N cells and P genes, we can define a Wishart matrix:

All the properties of W are described by its eigenvalues and eigenvectors in the form:

If X is a random matrix, then there are some universal statistical features:- Eigenvalue density follows the Marchenko-Pastur (MP) distribution

- The largest eigenvalue is described by the Tracy-Widom distribution

- Eigenvectors are delocalized

- Universality means that the statistical features are independent of the gene expression distribution. They only depend on the finiteness of the first few moments8,9.

More Detail

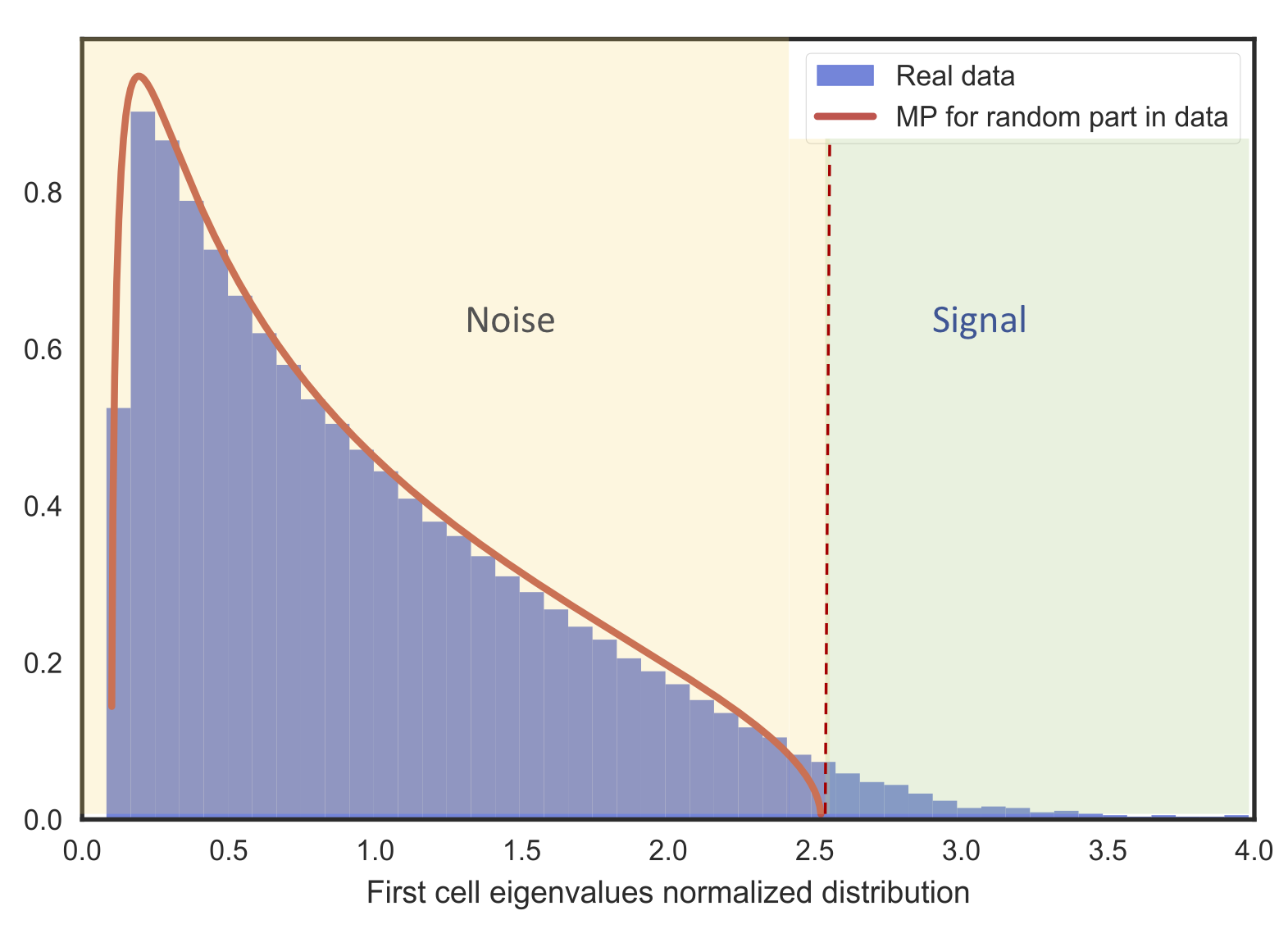

Deviations from the universal eigenvalue distribution (Marchenko-Pastur) predicted by Random Matrix Theory indicate the presence of a signal that can be further analyzed:

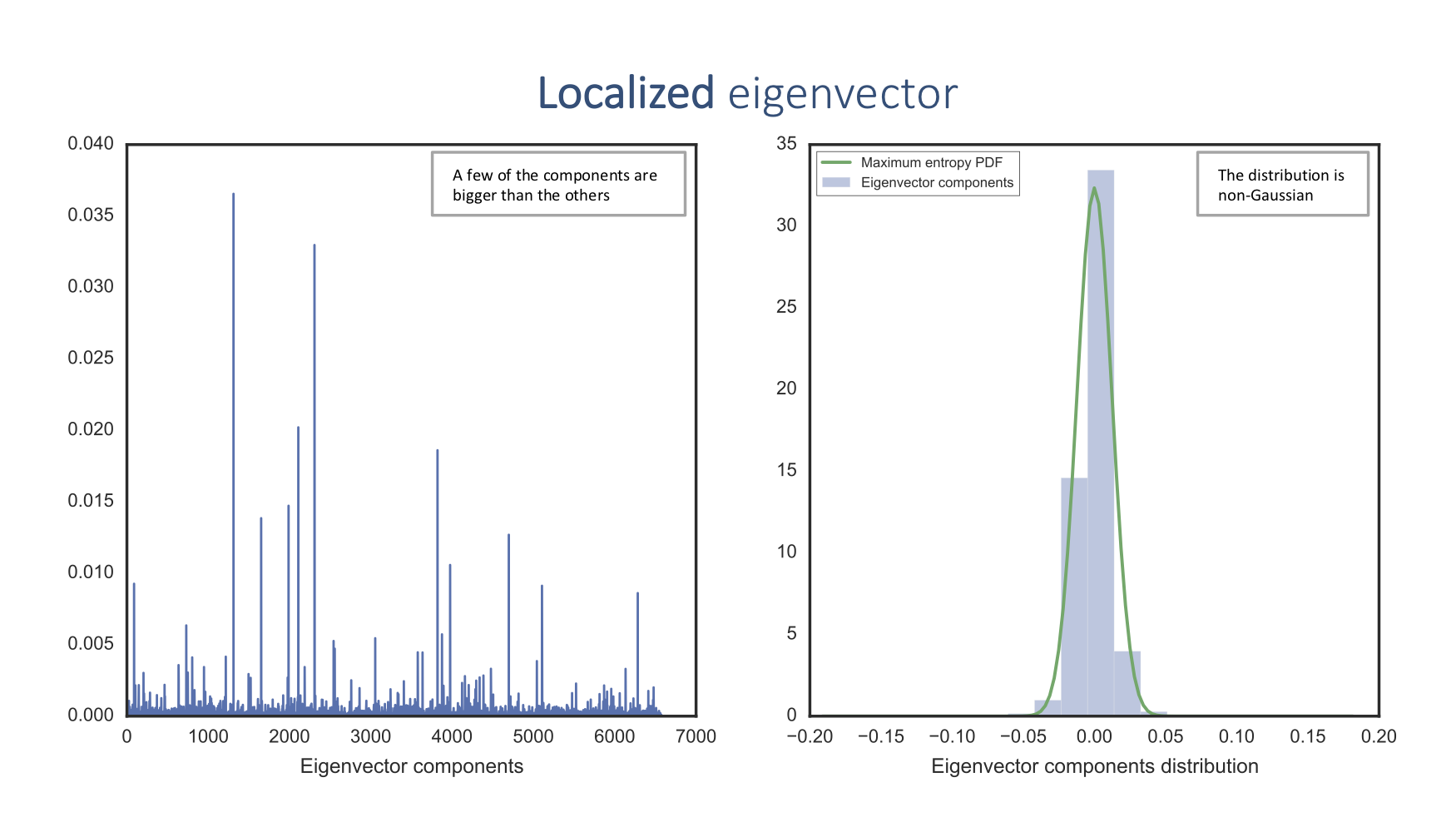

Equivalently, the appearance of localized eigenvectors indicates the presence of a signal:

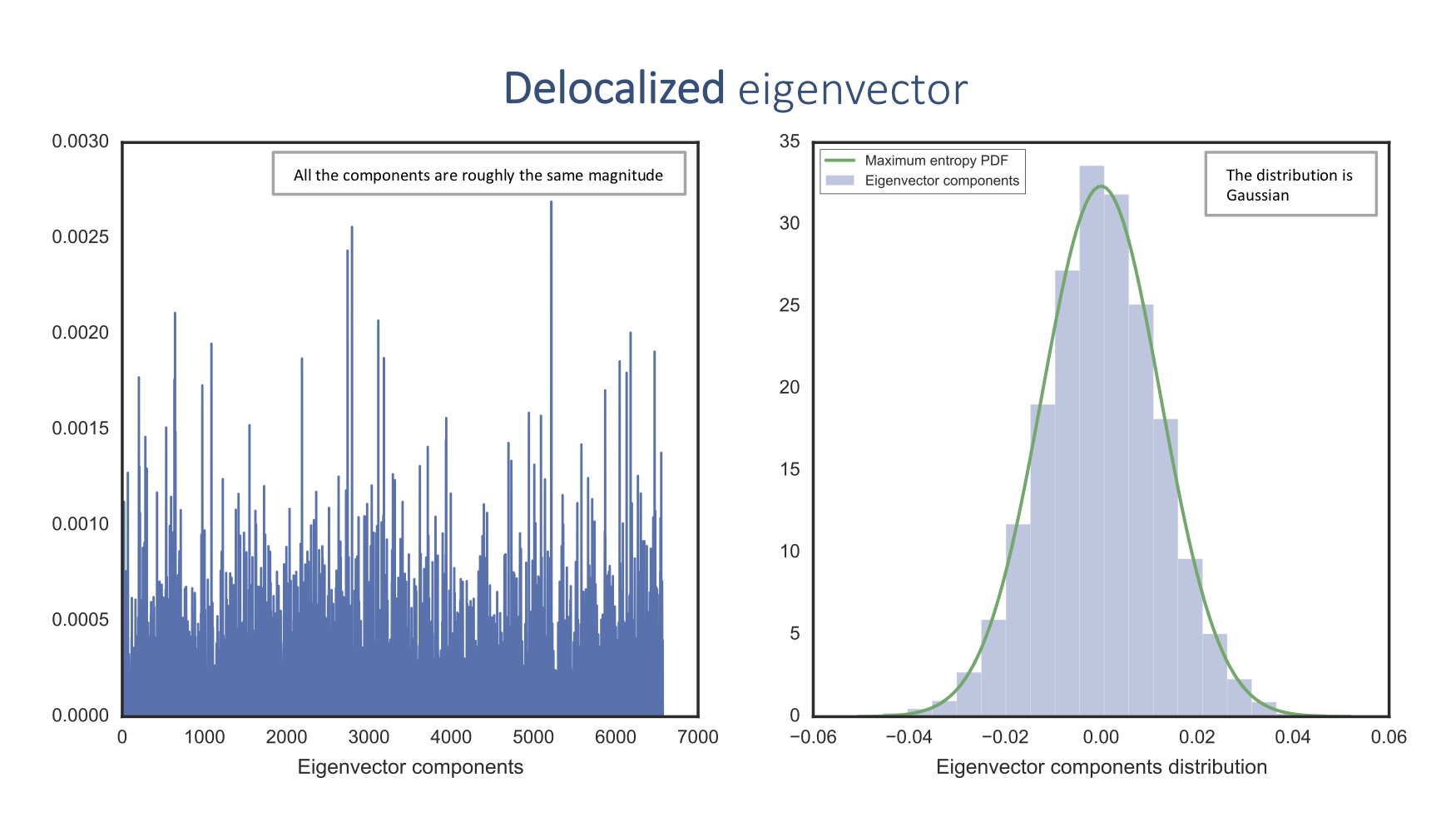

In contrast, the delocalized eigenvectors correspond to noise described by a random matrix:

The delocalized eigenvector component distribution corresponds to the maximum entropy probability density function (PDF), which means that there is no information. On the other hand, the localized eigenvector component distribution doesn't fit this PDF and thus contains information.

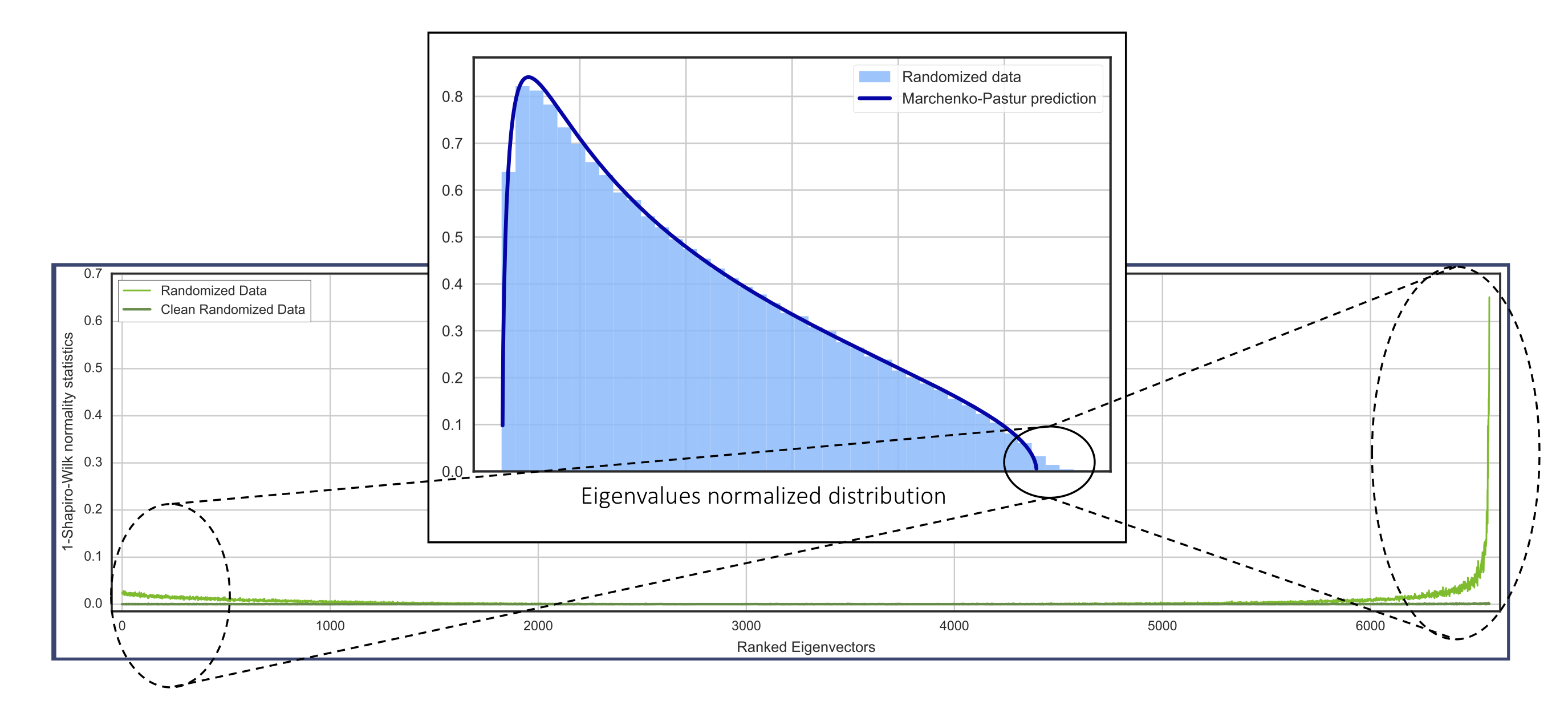

However, there is a subtlety: part of the signal is an artifact due to the sparsity of the data.

A way of capturing this artifact is to completely randomize the single-cell matrix. According to the theory explained above, all the eigenvectors should be delocalized and the eigenvalues should follow a Marchenko-Pastur distribution. However, the sparsity of the data modifies this predicted behavior. We call this artifact sparsity induced eigenvector localization. In the following plot, we apply a Gaussianity test to identify the localized eigenvectors corresponding to this artifact:

Eigenvector localization, which is an example of Anderson localization, is present in many physical systems, but has never before been reported in biological data.

The Takeaway

The take-home message is the following:

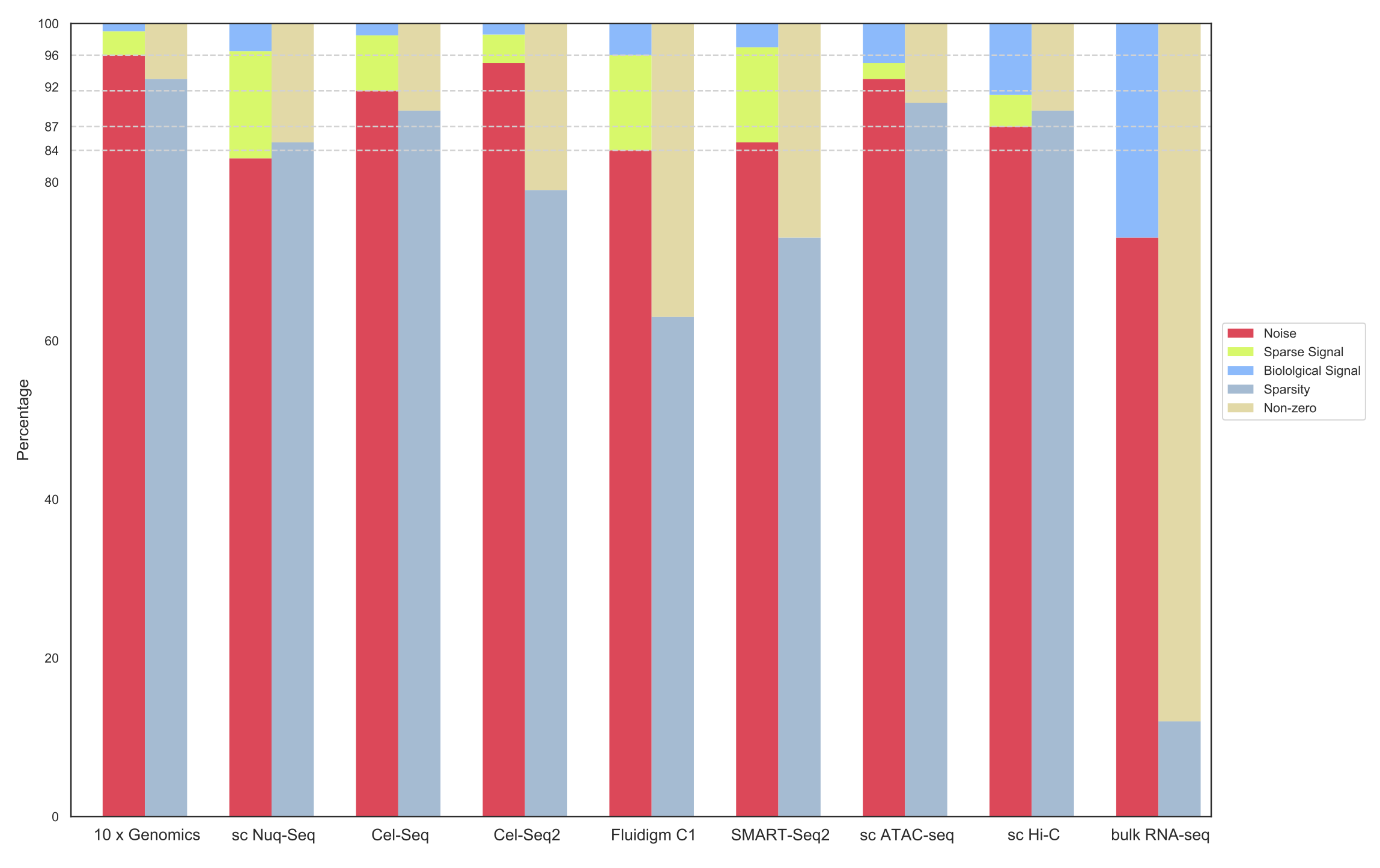

- Artifacts due to the sparsity of the data, including sparsity induced eigenvector localization, account for 3% of the signal eigenvalues on average.

- On average, the final 2% of eigenvalues could then be attributed to a true biological signal.

-

Universality of random matrix theory guarantees the validity of the method regardless of the single-cell technology:

- Sparse Random Matrix Theory and eigenvector localization provides an underlying mathematical framework to study many biological phenomena at the single-cell level. Technically speaking, we can say that single-cell biological systems behave like a perturbed sparse random matrix ensemble.

An Example

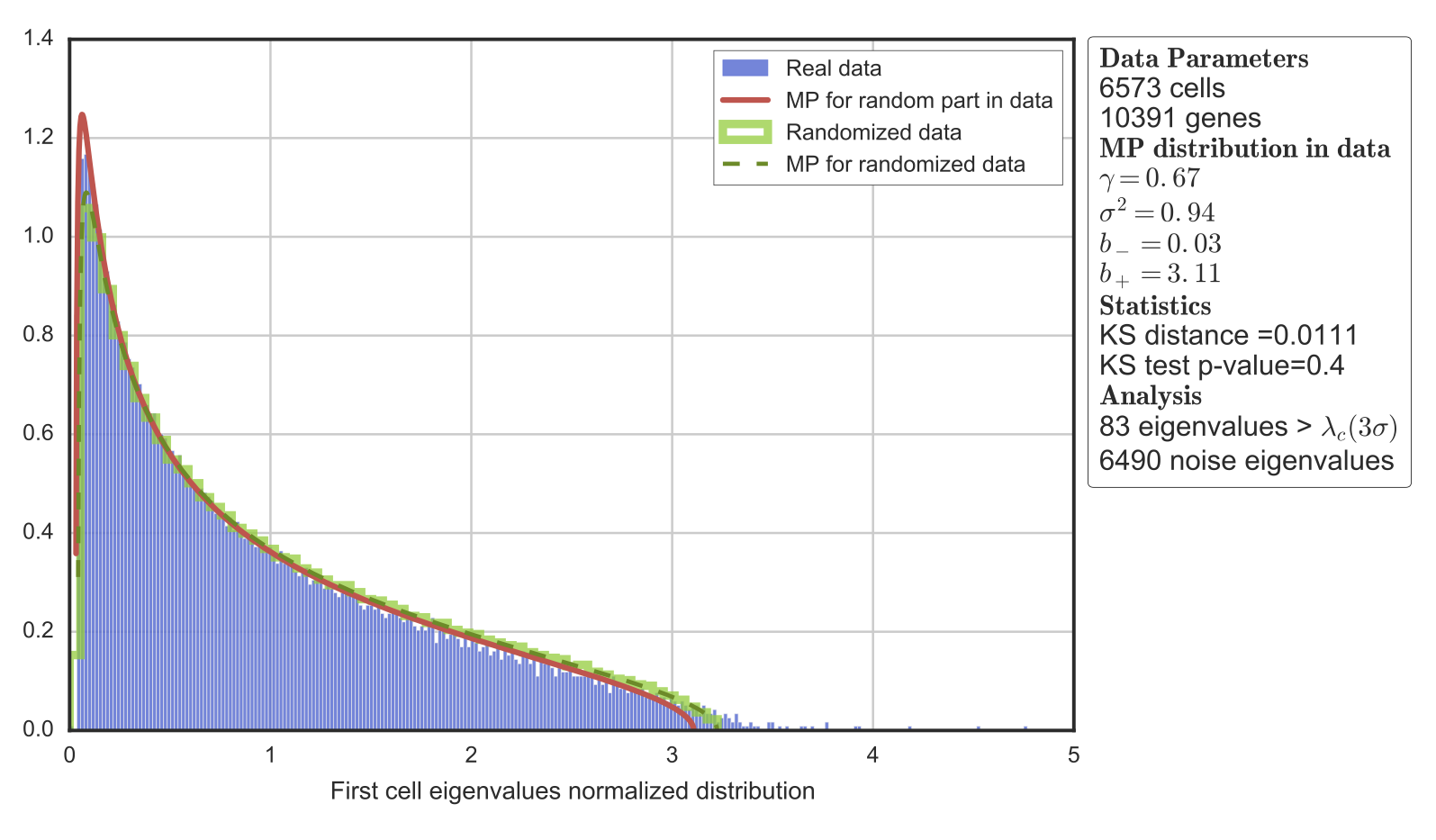

As an example, we consider single-cell transcriptomic data from a set of 6,573 peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC)12.

Randomly applies the universality features of Sparse Random Matrix Theory10,11 to separate noise and signal in single-cell data. The Randomly analysis consists of three main steps:

-

Separation of noise and signal using universality of MP and Tracy-Widom distributions:

- Removal of the sparse signal in the dataset by studying the sparsity induced eigenvector localization

-

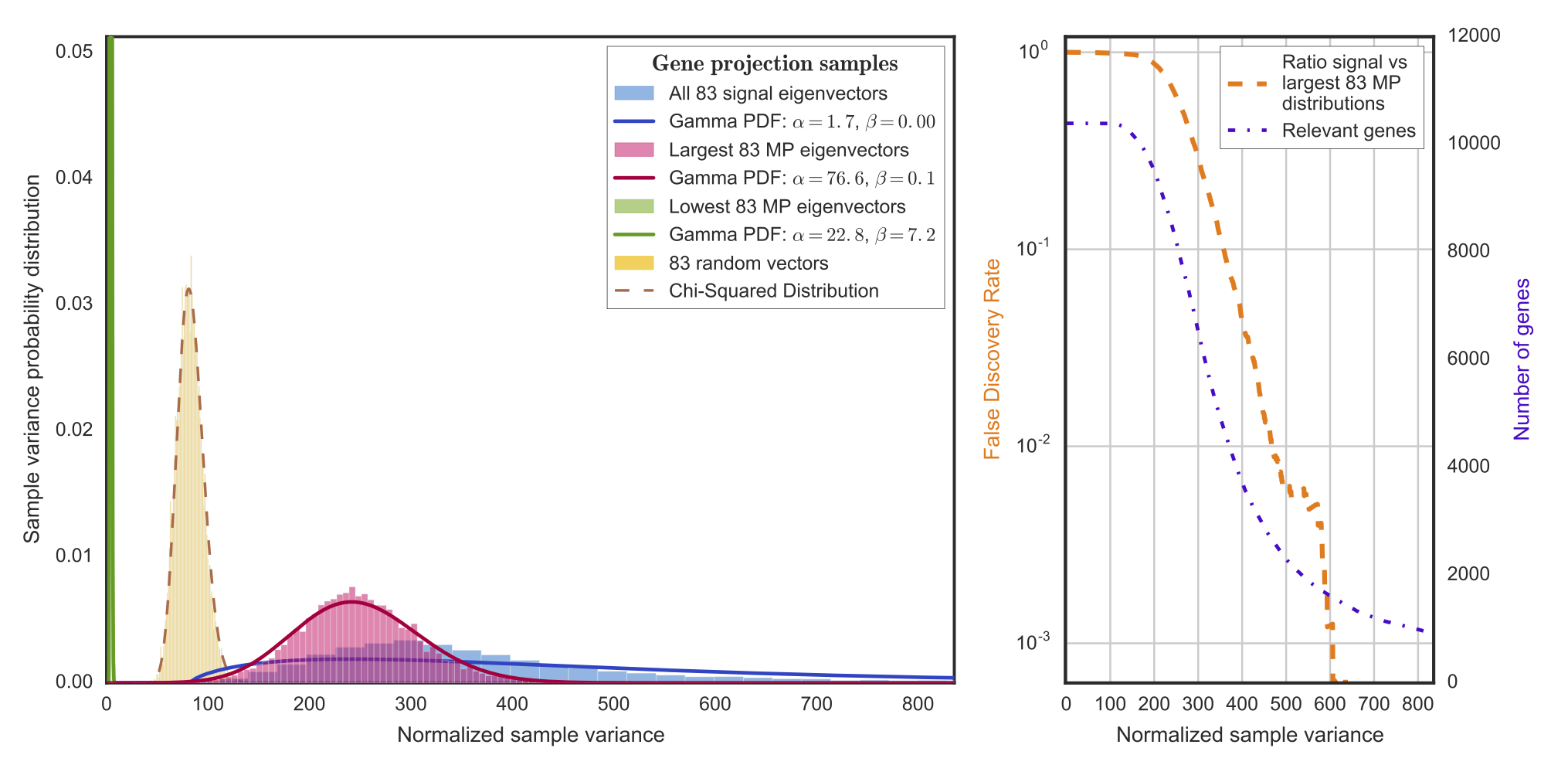

Selection of the genes which are most responsible for signal.

To accomplish this, we project the genes into signal and noise components, and then study the sample variance via a chi-squared test.

From that, we establish a false discovery rate to identify genes that generate signal:

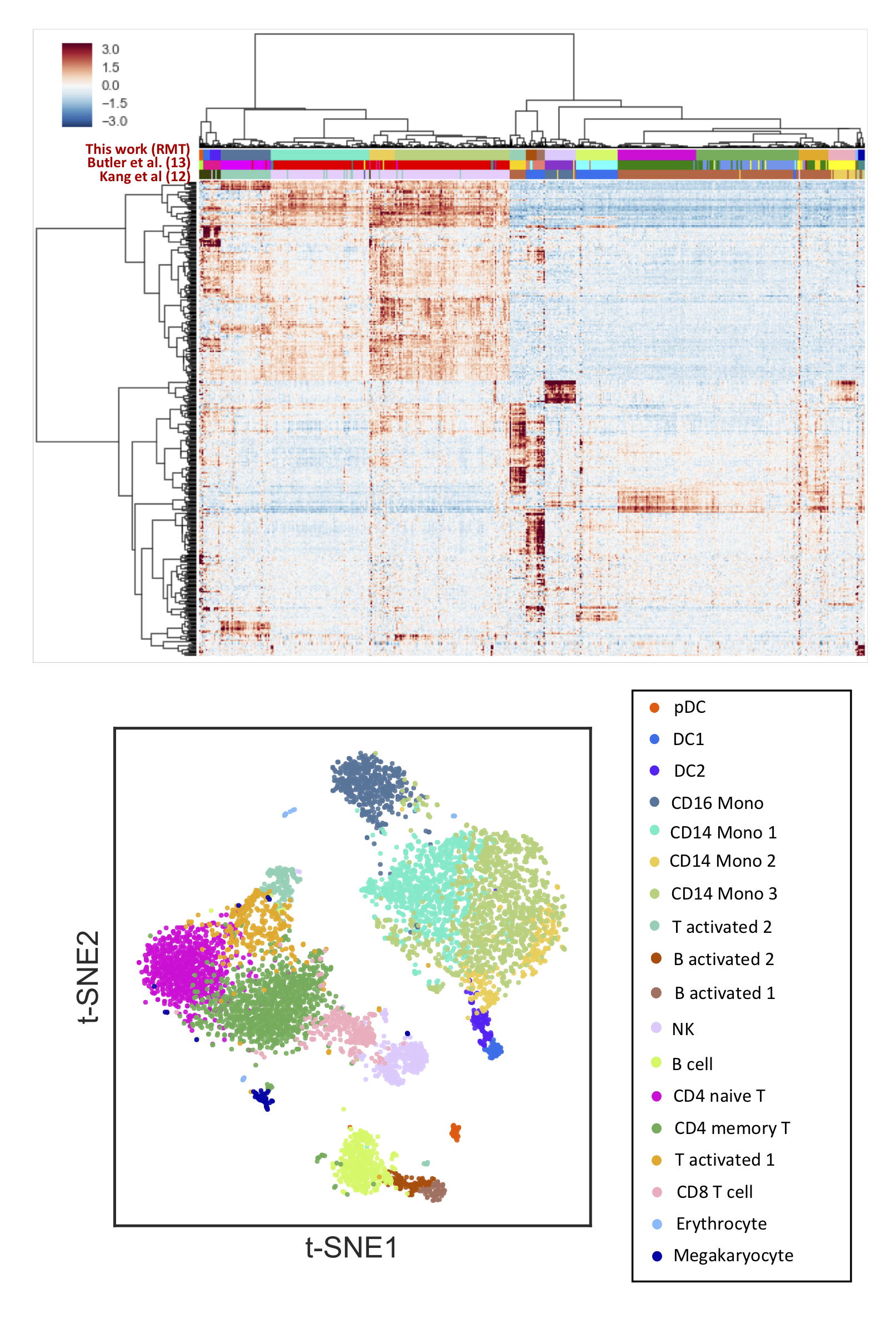

We have projected out the noise and selected the top 1,000 genes most responsible for signal according to the step just described.

We use these projected genes to do a standard hierarchical clustering and visualize it using t-SNE.

We compare our clustering with the cell labels provided by Kang12 and Butler13.

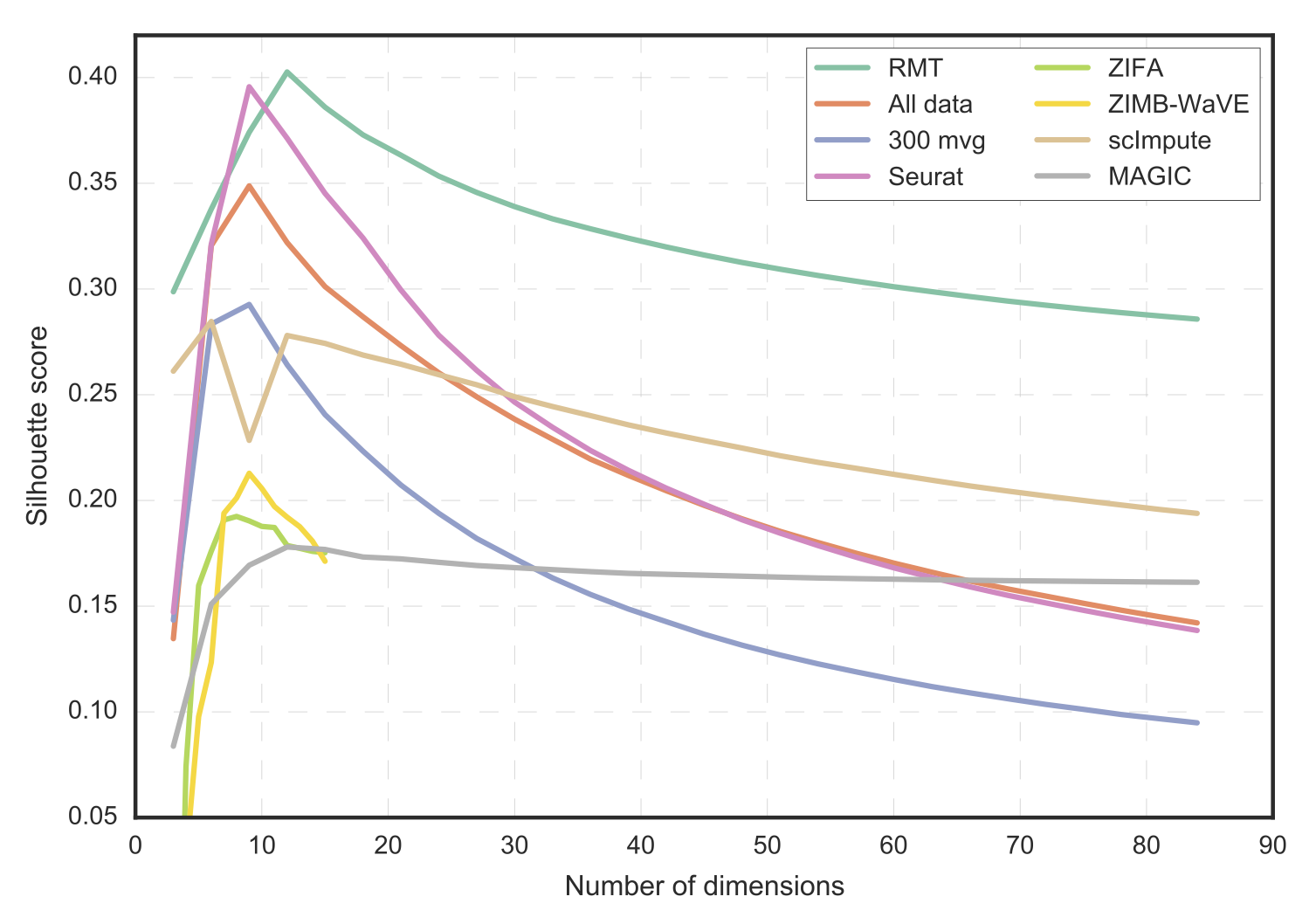

We compare the performance of Randomly (RMT) with other algorithms in terms of cell-phenotype cluster resolution.

For completeness, we also compare with the raw data and with a selection of the top 300 genes based on highest variance (300 mvg).

Provided known cell-phenotypes from Butler13, the mean silhouette score quantifies the cluster resolution.

The comparison is performed as a function of the reduced-space number of dimensions (number of principal components).

Randomly Interactive Demo

The following demo shows a t-SNE visualization of phenotypes of mouse-cortex cells provided in Zeisel et al.14 The clustering of cells is modified by changing the t-SNE parameters and principal eigen-components involved.

As we sweep across the range of eigenvalues, we can obtain either structured or completely random distributions.

Citation

For now, you can cite the Randomly preprint as:

Quasi-universality in single-cell sequencing data.Luis Aparicio, Mykola Bordyuh, Andrew J. Blumberg, Raul Rabadan.

biorXiv preprint doi.org/10.1101/426239 (2018).

arXiv preprint arXiv:1810.03602 (2018).

References

- L. Bintu et al., Dynamics of epigenetic regulation at the single-cell level. Science 351, 720-724 (2016)

- J. Cao et al., Comprehensive single-cell transcriptional profiling of a multicellular organism. Science 357, 661-667 (2017)

- D. van Dijk et al., Recovering Gene Interactions from Single-Cell Data Using Data Diffusion. Cell 174, 716-+ (2018)

- W. V. Li, J. Y. J. Li, An accurate and robust imputation method scImpute for single-cell RNA-seq data. Nat Commun 9, (2018)

- E. Pierson, C. Yau, ZIFA: Dimensionality reduction for zero-inflated single-cell gene expression analysis. Genome Biol 16, (2015)

- D. Risso, F. Perraudeau, S. Gribkova, S. Dudoit, J. P. Vert, A general and flexible method for signal extraction from single-cell RNA-seq data. Nat Commun 9, (2018)

- F. J. Dyson, Statistical Theory of Energy Levels of Complex Systems .1. J Math Phys 3, 140-& (1962)

- T. Tao, V. Vu, Random Matrices: Universality of Local Eigenvalue Statistics up to the Edge. Commun Math Phys 298, 549-572 (2010)

- N. S. Pillai, J. Yin, Universality of Covariance Matrices. Ann Appl Probab 24, 935-1001 (2014)

- Y. V. Fyodorov, A. D. Mirlin, Localization in ensemble of sparse random matrices. Phys Rev Lett 67, 2049-2052 (1991)

- S. N. Evangelou, E. N. Economou, Spectral Density Singularities, Level Statistics, and Localization in a Sparse Random Matrix Ensemble. Physical Review Letters 68, 361-364 (1992)

- H. M. Kang et al., Multiplexed droplet single-cell RNA-sequencing using natural genetic variation. Nat Biotechnol 36, 89-94 (2018)

- A. Butler, P. Hoffman, P. Smibert, E. Papalexi, R. Satija, Integrating single-cell transcriptomic data across different conditions, technologies, and species. Nature Biotechnology 36, 411-+ (2018)

- Amit Zeisel, Ana B. Muñoz-Manchado, Simone Codeluppi et al. Cell types in the mouse cortex and hippocampus revealed by single-cell rna-seq. Science, 347(6226) 1138–1142, 2015

- J.B. Garg, J. Rainwater, J.S. Petersen and W.W. Havens, Jr., Neutron Resonance Spectroscopy. III. Th 232 and U 238. Phys. Rev. 134 (1964) B985

- O. Bohigas, R.U. Haq, and A. Pandey, in Nuclear Data for Science and Technology, K.H. Bochhoff (ed.), Reidel, Dordrecht (1983), p.809